Chapter Three – Blue Moon

You may very well wonder, after the Caneel Bay fiasco, why I would ever think myself capable of owning a large sailboat. Easy. Time melted away the humiliation and the incident became a comical circus event suffered by my naïve younger self. Also, I became a prodigious reader of books about sailing. As it turns out, many sailing books skip the description of endless perfect days and instead regale the reader with misadventures. Poor Tania Aebi, in her enthralling book Maiden Voyage, knew almost nothing about sailing when she embarked upon a round-the-world solo journey. My antics by comparison to those I read about seemed pedestrian. I also believed I could book-smart myself into avoiding the usual pitfalls.

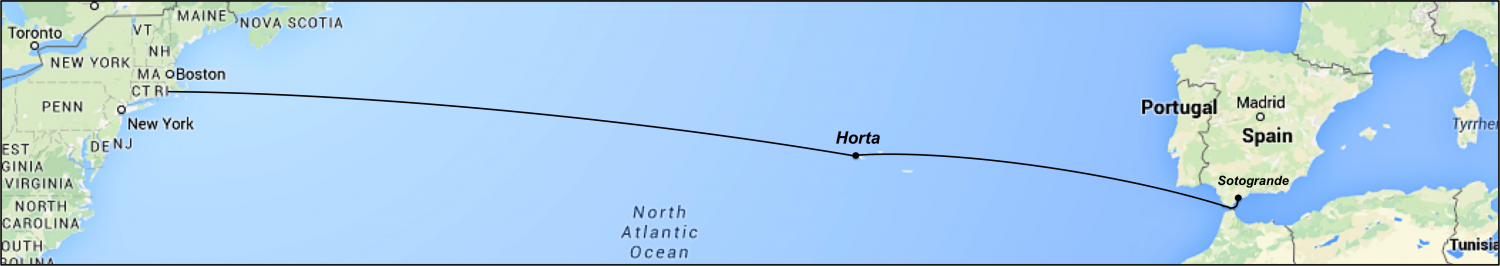

In 1992 I read the brilliant book Windfall by William F. Buckley. It is a captivating and often whimsical account of a trans-Atlantic sail with a close group of friends. It served as my inspiration for my next twenty years of sailing, up to and including my own Crossing and indeed this account. Buckley, one of my great heroes, back in the day when conservatives were found to be intellectual giants, instead of the opposite, had written three other books on sailing. I tracked them down and devoured them, each brilliant and charming.

By the mid nineties we were tossing our then four kids (pre-Annie days) into the back of our Suburban and trundling off to boat shows in Annapolis and Newport. We met at one of these a gentleman named Alan Baines, a convivial and experienced broker of Nautor Swans. As I pored through the glorious pages of Ferenc Mate’s The World’s Best Sailboats I kept returning to the description of the Finnish-built Swans and their electric blend of high performance sailing and bullet-proof construction. Alan called one day to say that a doctor had ordered a brand new Swan 40 but was unable to fulfill the contract due to business difficulties. If we were inclined to move quickly we could secure this lovely craft at a meaningful discount. We took the plunge. Blue Moon, as she was to be named, was shipped over from Finland and trucked up the Eastern coast to the redoubtable Jamestown Boat Yard. She was re-rigged and we had one test sail before taking possession. We had her white hull painted a beautiful flag blue. She had teak decks and a cherry interior and was a beauty to behold.

To say I was nervous about sailing this boat would be a colossal understatement. My prior boat ownership had consisted of the 50-pound Scamper. I had sailed on the ocean only once, in forgiving Virgin Island waters, to ill acclaim. Compounding the matter, I decided that my maiden voyage would be with a handful of business colleagues, none sailors, from Jamestown, Rhode Island to Nantucket. This 70-mile voyage, which I was to repeat over 40 times through the years, was through some tricky currents, invisible shoals and dense fog banks. This was before they had chart plotters, the GPS maps now found in so many cars, so we actually had to do a bit of navigation. The first voyage had no disasters and only one near miss. I had gone below and left a colleague at the helm, steering toward Vineyard Sound with the wind more or less from behind. Suddenly I heard a CRASH, as the boom slammed across the boat. I scampered on deck and shouted at him “Do you realize what you just did? That was an accidental gybe, one of the most dangerous things you can do in sailing!” I cringe as I recall the mishap – in truth it was every bit my fault and none of his. I should have never left him at the helm. More to the point, I should have never been sailing off the wind without rigging a “preventer”, or a line from forward securing the boom from exactly this maneuver.

The sea has kindly taught me these lessons slowly and patiently, with no real injuries. Over the years we had many family adventures on Blue Moon, exploring the waters around Nantucket and Cape Cod. The failings and scrapes came in small digestible doses and taught me, gradually, how to be a sailor. Michael Henry was just under two years old when he first set foot on her. I had convinced Mary he would be safe because we would confine him to the aft cockpit, always within reach. This lasted almost two minutes, whereupon he stubbornly clambered up the side deck. At least he was tethered to the boat. Sarah, Matthew and William were eight, six and four at their first sail and developed sea legs almost immediately. I have vivid memories of them sitting on the tiny bow seat, like a dunking chair, as we crashed through the “big waves” left by the ferry in the Nantucket channel.

Annie took her first sailing trip as a fetus. We sailed from Nantucket to Block Island, stopping over at the tiny island of Cuttyhunk on the way. As we left the relative protection of Vineyard Sound and headed to Block Island, we encountered gentle-but-giant ocean swells. The kids thought these to be great fun. Mary, who tends towards seasickness in the best of circumstances, was pregnant with Annie. She lay prone on the side-deck, moaning. Somehow the teak deck against her cheek made the conditions tolerable, if barely. To reward her composure we booked a hotel room in Block Island, with air conditioning. My family has never been so delighted with a hotel room. We lined up roll-aways across the room to form one continuous bed and cranked the AC and delighted in our creature comforts. It was a lesson I was to learn again and again, that sailing must be interrupted by other activities to be fully enjoyed by the crew, conscripted as they were.

I keep a mental top-ten list of best-ever sails. One of my favorites occurred during another Newport-to-Nantucket trip aboard Blue Moon. This particular Spring I had five friends on board. Only one had any sailing experience. We had a pleasant first day featuring beers and gentle breezes en route to Vineyard Haven harbor, where we picked up a mooring for the night. The next morning I was awakened at six by the wind positively howling in the rigging. I gingerly stuck my head out of the main hatch to survey the seascape. The tiny harbor was whipped into a frenzy of whitecaps. I promptly retreated to my berth and fell back to sleep, scotching the plans for an early Nantucket arrival. Several hours later, wind still a-howl, we donned our foul-weather gear and chugged our way to the dock in our dinghy. The forecast was for gale-force winds and intermittent rain, diminishing in the late afternoon. I explained over breakfast to the crew that we were in in the protected waters of Nantucket Sound with a worthy vessel. The sail to Nantucket, while not expected to be dangerous, might not be everyone’s idea of fun. Two of the crew opted out and took a ferry to Woods Hole. This was a good choice for them, and for me. Sailing in trying conditions is markedly more stressful with anxious, unhappy or seasick crew.

The remaining four of us returned to Blue Moon and readied for action. We had some very tense moments getting under way. The wind was blowing 35 knots and gusting to 40. As we dropped the mooring a gust caught the bow and thrust her over towards the boat on the adjacent mooring, exposing more of our hull to the searing wind. Turning a rudder, it needs to be said, does no good at all unless there is water moving across the rudder. This can be effected by moving the boat or by spinning the propeller, located as it is just forward of the rudder. I gunned the throttle of the 90 horsepower diesel and turned the rudder all the way to our left, upwind and away from our neighbor. For a moment it looked like we would simply crash, our bow swinging dangerously in the direction of the next boat, but gradually the force of the water over the rudder asserted itself and the bow turned slowly windward, battling back the wind and away from trouble. We cleared the mooring field and headed out.

Once clear of all other boats, we headed into the wind and raised the mainsail. With so much wind, we needed to raise a smaller mainsail, lest we become hopelessly overpowered. This entails putting in a reef, or on this case a double reef. The reef is accomplished by simply attaching the sail to the boom at alternate tie-rings, located five or ten feet up on the mainsail at the front and the back (or tack and clew). The sail then makes a smaller triangle, with the top of the sail only two-thirds of the way up the mast, or less. In this way one mainsail can be used full-sized, reefed, or double reefed, effectively giving you large, medium and small sails all in one. Boats use different types of systems for attaching the tack and clew at reef points. Blue Moon deployed a single line system, supposedly simple to engage but in reality extremely difficult in that it never got the tension just right at both attachment points. We had a stressful time securing these points, and I sheepishly admit to yelling at John, the other sailor on board who was tasked with getting the sail up. The operation was rendered more arduous still by the horrific and deafening flogging of the mainsail as we headed dead upwind to get the sail up.

Once properly double-reefed, we headed gently downwind (or bore off). The dastardly flogging ceased altogether and we began magically sailing in the Sound. We unrolled about three feet of the jib to balance out the rig and spirited away, beaming with pride. There were absolutely no other boats on the sound. Because we had the sails properly sized for the wind, Blue Moon scooted along at hull speed with nary a complaint. Even in the sheltered Sound, we had waves breaking over the bow and washing all the way back on the deck to the spray dodger, which diverted the water to the side decks and kept us safe and dry. We felt like we had both conquered nature and become one with her. As the day wore on the winds diminished. We shook out the double reef and made the final turn around Tuckernuck Shoal with sunny skies and 15 knots of breeze and a genuine glow of accomplishment.

You forgot that on that Block Island sail, not only were the swells huge, but the fog was so thick, that we could not see the passing boats until they were extremely close. Seems there might have been a shipping lane as well?

Love you, miss you. Have fun and please stay safe!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right! I will polish this up with your help remembering. Love you!

LikeLike

“A smooth sea never made a skillful sailor.⚓️”

Is a quote that seems to apply to this chapter.

LikeLike

You are gifted. Thank you for this opportunity to read a ‘classic’ in the making. Your descriptive, humorous prose transports us to the time and place. We’re awaiting Chapter 4!

LikeLike